What do cattle and sheep have in common?

Posted on February 26, 2024 by Lee Schulz

Source: Farm Progress. The original article is posted here.

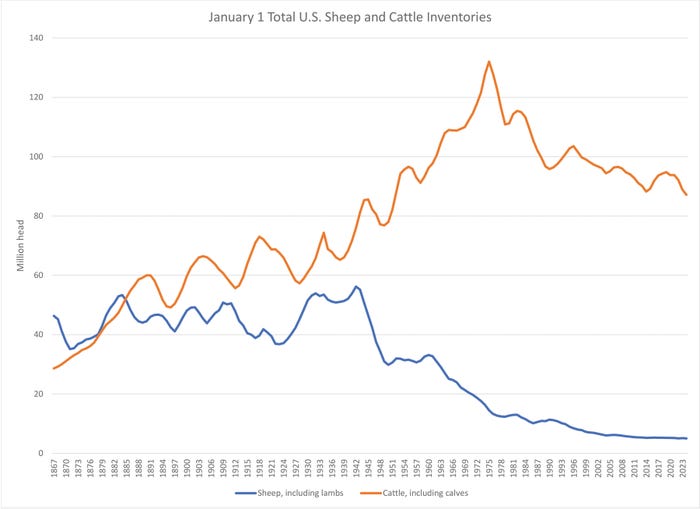

The Jan. 1 U.S. inventory of all sheep and lambs totaled 5.03 million head. This is the smallest sheep and lamb inventory ever. USDA provides the series back to 1867.

All U.S. cattle and calves on Jan. 1 totaled 87.16 million head. This is the smallest inventory of cattle and calves since 1951. The 28.22 million beef cows are the smallest since 1961. Despite fewer cows, beef production per cow continues to rise.

USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service compiles inventory estimates based on producer responses to surveys. NASS survey procedures ensure that producers, regardless of size, have a chance to be included in each survey.

Both cattle and sheep industries have distinct growth and liquidation cycles. Inventory cycles are measured from one trough to the next. The current cattle cycle and sheep cycle began in 2014. Both entered their 10th year in 2024.

Factors driving cycles

Sheep and cattle have similar nine- to 14-year inventory cycles. Cycles result from lagged responses created by both biological and economic phenomena.

One might expect sheep to exhibit shorter inventory cycles than cattle because of shorter gestation (about 147 days for sheep versus 283 for cattle), multiple births or twinning, and shorter time from birth to market. These production characteristics apparently do not create a shorter sheep inventory cycle. Weather abnormalities often initiate or modify livestock inventory cycles.

Cycle length in both species has generally shortened over time. Amplitude of cyclical inventory changes has also decreased. Several factors may contribute. They include:

technological advances, especially in reproductive and feeding efficiency, that speed production response to changes in prices

enhanced market reporting and information gathering and dissemination that may improve producers’ decision-making ability

increased responsiveness of producers and markets to economic pressures, brought about by increasing costs and volatile output prices

While the amplitude of cyclical inventory changes has decreased, the opposite has occurred with price movement. Cyclical behavior for prices is typically more erratic than for quantities. Historically, demand for cattle and sheep has been fairly inelastic. This leads to cycles characterized by a greater percentage change in prices relative to quantities. Large changes in prices across the inventory cycle intensify financial uncertainty and boost risk for producers.

These price gyrations affect all segments of the industry. But the price swings may have different effects and timing on cow-calf producers than on stocker and backgrounding operators, or on cattle feeders. The same goes for stock sheep producers and lamb feeders.

Efficiency in good times

One key to thriving through price swings of inventory cycles is to increase efficiency during good times. Then, use this gained economic efficiency to build a financial reserve to survive the next downturn in prices.

No one can perfectly predict how high or low prices will go and when the cycle will turn. The challenge for producers is to anticipate the price cycles and adjust their production accordingly.

SHARED RESOURCES: Sheep share many of the same resources with cattle. These include grazing land, labor, facilities and transportation. (Nicolas Tucat/Getty Images)

Tough times call for focusing on management. In reality, producers often make their most important decisions ― sometimes good, sometimes bad ― during good times.

Diversification may help

Cattle and sheep have historically competed for many of the same resources. These include grazing land, labor, facilities and transportation. Some multi-species grazing synergies exist with cattle and sheep. Cattle and sheep working the same ground can use the pasture, labor and other resources more fully. Both animals eat grass. But sheep eat more brush and forbs. They graze more selectively and lower in the pasture stand.

Diversifying can make a farm less vulnerable. If the market price for one product, say cattle, falls or doesn’t promptly respond to higher costs, then another product, say sheep, may compensate for the lower income.

How much diversification may reduce income variability depends on the price and production correlations of the enterprises. If prices or production for both enterprises tend to move up and down together, diversifying gains little. The more production and/or prices of different products move in opposite directions, the more diversifying may reduce income variability.

How much diversifying can smooth income depends on the proportion of income derived from each enterprise. If only a small proportion of income comes from one product, it can do little to support income if the primary product market collapses.